When people think about play-based learning, if they can name any particular discipline at all, it’s usually Montessori. But in my opinion there’s a better, less well-known learning approach that also started in Italy and is now used worldwide.

In my 13 years of teaching experience, I think Reggio Emilia is the best learning approach for early years education and is actually vital for childhood development.

What is Reggio Emilia?

Reggio Emilia is named after a small town in Italy. After WW2, Italy was trying to get as far away from fascism as possible and instead turned to socialism and communal approaches, especially when it came to educating their children.

Inspired by the self-managed educational approaches developing in schools located in the Reggio Emilia countryside, a pedagogy scholar and psychologist named Loris Malaguzzi decided to open the first Reggio preschool in 1963. Malaguzzi invited the community to help shape the school and had many community debates over how to best teach the children of the town.

This communal approach to teaching still exists in Reggio Schools to this day.

Why is Reggio Emilia Better?

I prefer Reggio over other approaches because each child is given full autonomy over their learning journey.

The focus is placed on the child and what they want, not on what the teacher and schools want the child to be. The teacher is not an authority figure like in typical schools and even in Montessori classrooms. Instead, a Reggio Emilia teacher is a facilitator of learning who encourages and guides each student based on their individual interests, needs, and passions.

This means there aren’t any lesson plans, there isn’t any homework, and there aren’t any worksheets EVER! The teacher doesn’t tell the students what to learn. It’s up to each student to choose what to explore, what questions to ask, and what activities to do.

“But then what do the kids do all day?”

Yes, I used to get that question a lot from parents who were just starting on a Reggio Emilia journey with their child.

ALSO: Apply the Reggio Emilia Approach at Home

You see, I taught at a Reggio Emilia preschool for 4 years in Bangkok, Thailand. My students were from all over the world, so they came from various cultures and parenting styles.

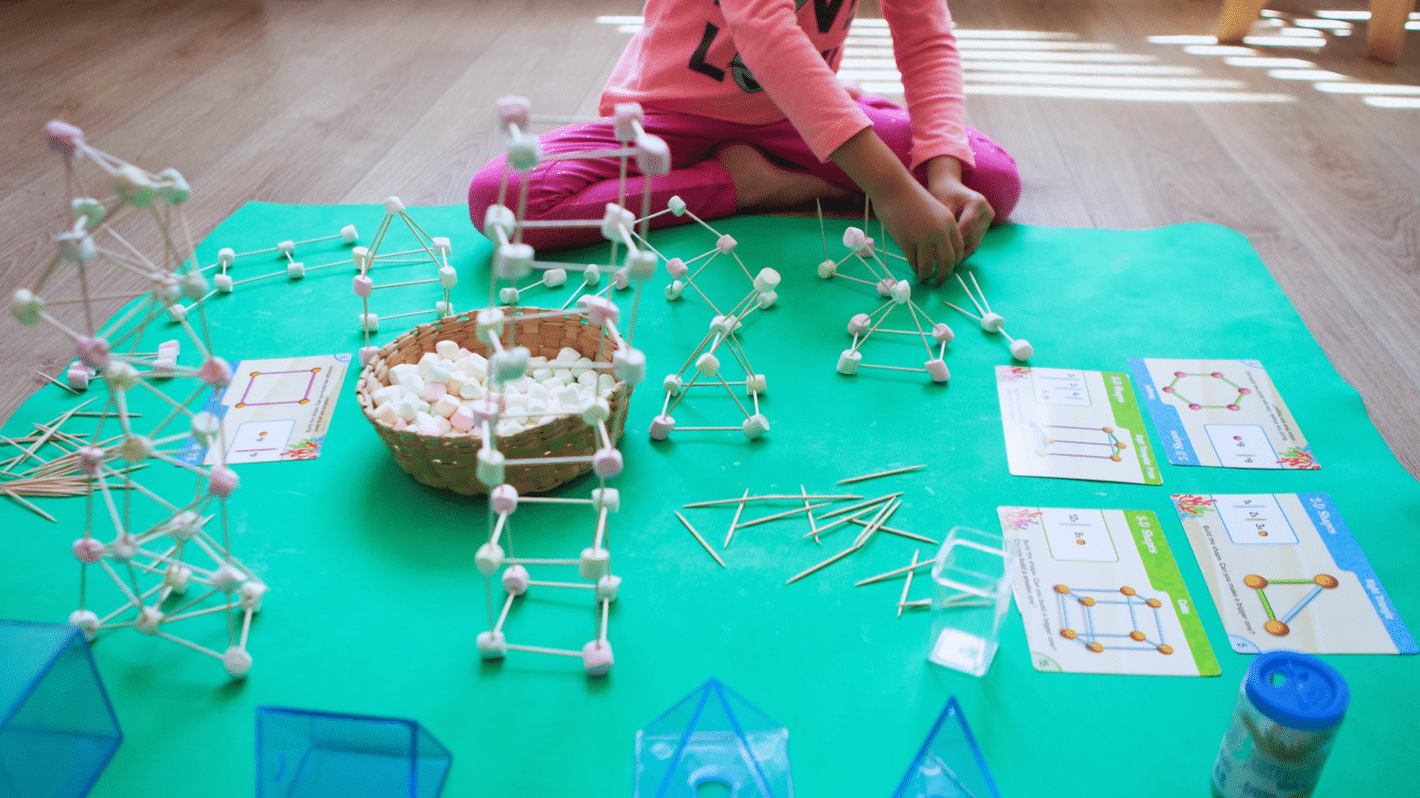

Every single one of them loved school and became confident, imaginative, social, and inquisitive about the world around them. Instead of being told to memorize things based on a lesson plan, my students spent the day exploring, playing, making art, and socializing.

I had students who loved the toy animal area. Other students loved building things with blocks and would make large sculptures that looped around the room. Other students would spend most of their time reading books in one of the various reading areas around the learning space. I noticed that my more adventurous and outgoing students loved the light table and projector.

My students also had water play once a week where they explored an outdoor water area and they also had a messy outdoor activity like playing with spaghetti dipped in food coloring and throwing it on themselves and each other. On top of that, they had outdoor play in a garden with a playground and hedge maze but they spent as much time outside as the hot and humid weather would allow.

“So, what do Reggio students learn if they’re just playing all day?”

Through play, they’re developing their language skills, learning social skills, improving their fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination, improving their balance, and more importantly, they are developing their confidence, imagination, and critical thinking skills. They would not be able to do all that if they spent most of the day sitting at a small desk in rows facing the teacher who is telling them what to think and do.

Traditional Classrooms Are Outdated

To really understand what Reggio is and why it works so well, it’s important to understand how outdated and mentally limiting a traditional classroom is.

First, let’s look at the space. In a traditional preschool and kindergarten classes, there are toys and play areas but there is also a huge whiteboard and little desks and chairs facing that board so the teacher can tell the students what to think and what to memorize that day.

The traditional classroom is only one boxed room. so these kids are stuck in one rectangular space all day with some limited, prescheduled, outdoor play and maybe a trip to the cafeteria if the school has one, otherwise they have to eat in that box too. There are also student worksheets and printed posters on the walls with generic stuff like the alphabet and target vocabulary words with pictures in perfect rows.

Reggio Classrooms Are Very Different

A Reggio class has various centers with different natural and human-made materials for children to explore at their leisure. There are no worksheets and no printed things on the wall. Instead, the walls are decorated with the children’s art and pictures of them. The only posters are Reggio project posters which show students exploring a certain theme like “light and shadow” or “water” from previous years.

ALSO: Parenting Style — Are You Authoritative, Permissive, or Authoritarian?

Instead of homework, Reggio students have in-class projects that they work on for the entire year. Older students can pick their projects but for younger students, the teachers pick a theme and take pictures and videos of the kids exploring the theme and take note of how that theme develops over the school year.

Teachers take note of everything and take lots of pictures and videos to show parents and document the child’s interests and special moments throughout the year.

Instead of being trapped in a shoebox, like I was when I taught in a traditional classroom, I had a huge common area plus two large rooms for the students and I to explore. Not all Reggio schools can offer that cushy setup, it really depends on the building the school is in. My school happened to be in a two-story house with a huge garden and backyard, so my “classroom” looked like a mix between a home for little people and an avant-garde art installation. I was able to decorate however I wanted and set up any kind of center I wanted. The freedom students have in a Reggio environment also extends to teachers as well.

This freedom is extremely important, especially during the early years of human development. A child’s first six years of their life are the most important years. What happens during these years and what they are taught will shape their minds and personalities for the rest of their lives. That’s why it’s so important that they learn in a way that promotes confidence, critical thinking, empathy, and imagination.

ALSO: Does Self-Directed Learning Breed Success?

I’ve taught in traditional classrooms and was miserable, but tried to make it as fun for the kids as possible. I even quit one teaching job after two months because they put me in a small prison class and wanted the kids to only do worksheets, even when creating art!

When I put the kid’s art up on the walls instead of generic printed posters, I was told my class “looked messy.”

Thankfully, as soon as I quit that job, I was hired at a Reggio school and it really opened my eyes to how awful traditional classrooms and styles of teaching are. In a traditional setting, kids are only learning to conform and follow orders. That’s why so many have problems focusing or develop behavioral issues in class and at home, they have all this pent-up energy and stuff they want to express but they can’t in that kind of environment.

Malaguzzi’s poem, “100 Languages” best sums up the philosophy of Reggio Emilia:

The child

is made of one hundred.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.

A hundred always a hundred

ways of listening

of marveling of loving

a hundred joys

for singing and understanding

a hundred worlds

to discover

a hundred worlds

to invent

a hundred worlds

to dream.

The child has

a hundred languages

(and a hundred hundred hundred more)

but they steal ninety-nine.

The school and the culture

separate the head from the body.

They tell the child:

to think without hands

to do without head

to listen and not to speak

to understand without joy

to love and to marvel

only at Easter and Christmas.

They tell the child:

to discover the world already there

and of the hundred

they steal ninety-nine.

They tell the child:

that work and play

reality and fantasy

science and imagination

sky and earth

reason and dream

are things

that do not belong together.

And thus they tell the child

that the hundred is not there.

The child says:

No way. The hundred is there.

–Loris Malaguzzi (translated by Lella Gandini)